- Home

- Alexander Waugh

Fathers and Sons

Fathers and Sons Read online

Praise for Fathers and Sons

“A wonderful critical-loving job … a stupendous story.”

—V. S. Naipaul

“Very funny … as good as a great novel in its depiction of the human condition as embodied in the relationship between father and son.”

—Katherine A. Powers, Boston Globe

“All fathers and sons should read it.”

—Humphrey Carpenter, Sunday Times

—William Boyd, Guardian

“Written with wit, great shrewdness, and without a trace of sentimentality.”

“An absorbing study of how writers process their most painfully formative experiences.”

—Publishers Weekly (starred review)

—Michael Dirda, Washington Post Book World

“Histrionic lives that are great fun to read about.”

“Literary skill really does seem to be hereditary… Altogether an extraordinary story, admirably told, which leaves you thinking at the end what a remarkable family the Waughs are.”

—Geoffrey Wheatcroft, Daily Mail

“One enters the house of Waugh with trepidation and leaves with regret.”

—Harold Evans, Wall Street Journal

“A remarkable work of family history, exceptional for its honesty, inventiveness, humour, and for the beguiling individuality of its author's voice… Alexander Waugh proves himself outrageously graceful and accomplished with a talent that needs no help at all from his illustrious forebearers.”

—Selina Hastings, Literary Review

“[Evelyn Waugh's] grandson has given us another way to see his life and oeuvre, with a level of skill that everyone in the family would have appreciated.”

—Miami Herald

“Told with humour and panache, with considerable inside knowledge and a perception that makes this remarkable chronicle a delight to read.”

—Spectator

“Waugh relights the family's literary torch… huge fun.”

—Tatler

For Bron

CONTENTS

Family Tree

I Pale Shadows

II Midsomer Norton

III Golden Boy

IV Lacking in Love

V Out in the Cold

VI Spirit of Change

VII In Arcadia

VIII No Uplifting Twist

IX Happy Dying

X Irritability

XI Fantasia

XII Under Fire

XIII Leaving Home

XIV My Father

To Auberon Augustus Ichabod Waugh

Acknowledgements

Bibliography

I

Pale Shadows

I shall begin with a telephone call. It was half past seven on the morning of 17 January 2001 – annus horribilis – when I was woken by the ringing.

‘He's dead,’ my mother said.

‘I'll be right over.’

Quivering with excitement I told Eliza to break it to our children and to ring her father who, as planned, would act as conveyor of this dread information to the press.

Fifteen minutes later I was at Combe Florey, turning under the Elizabethan archway, looking up at my father's house. Unless I am very much mistaken, it was sulking. A gaping ambulance was parked by the perron. My elder sister was waiting for me by the front door. In the kitchen I was greeted by my mother and two sheepish paramedics. All three were ashen. Then the telephone rang – already, the first shoot of my father-in-law's grapevine: reporters from the Press Association seeking verification and a quotation.

My mother answered: ‘It is hard to sum up someone so wonderful,’ I heard her telling them, ‘but I've been hanging around for forty years, so that says something.’

I slunk out of the kitchen and shimmied up the stairs.

In his room the curtains were drawn, but there was just enough light to acknowledge the effect: open mouth, closed eyes; face a tobacco-stain yellow. The spectacle was disconcerting but, for the first time at least, I understood what ‘He's dead’ really meant. I sat on the armchair facing his bed and, for a short while, thought about death, endings, termini… There was no communication between us, not even in my imagination, and after a couple of minutes the stillness of the room began to oppress me. Now what? I wondered. A prayer? Should I speak to the corpse? Am I supposed to touch it?1

‘No. That is not Papa, just a gruesome remnant.’ I slunk back down the stairs to the kitchen, glad, at least, that I'd seen it.

The night before was the last time we had talked together. There was a brief exchange, until he lost consciousness.

‘Ah, a little bird has come to see me. How delightful!’

‘No, Papa it's me. I suppose you must have thought I was a bird because I was whistling as I came up the stairs.’

‘It's a bit more complicated than that,’ he replied, with a hint of the old twinkle.

I could not be surprised that the last words he spoke to me were intended as a joke: he was always funny, but those drawn-out deathbed days were – despite our finest efforts – not particularly amusing. It is not true that the dying are more honest than the living – I agree with Nietzsche about that: ‘Almost everyone is tempted by the solemn bearing of the bystanders, the streams of tears, the feelings held back or let flow, into a now conscious, now unconscious comedy of vanity.’

‘Everything is going to be dandy,’ Papa had insisted, as he lay uncomfortable and bemused with the skids well underneath him. ‘Isn't life grand?’

On the next day the papers were full of it: ‘Waugh, scourge of pomposity, dies in his sleep,’ trumpeted The Times; ‘End of Bron's Age’ was the Express's more comic effort. His death was lamented by the Australians on the front of their Sydney Morning Herald, by the Americans with long obituaries in the Philadelphia Inquirer and the New York Times (‘Auber on Waugh, witty mischief maker, is dead’), and as far afield as Singapore, India and Kenya. At home, all of Fleet Street rallied. Even the tabloid Sun, victim of his mockery for over three decades, sounded a plucky Last Post. Here is a typical broadside from earlier days:

The Sun's motives in whipping up hatred against an imaginary ‘elite’ of educated cultivated people are clear enough: ‘Up your Arias!’ it shouted on Saturday in its diatribe against funding which put ‘rich bums on opera-house seats.’ If ever the Sun's readers lift their snouts from their newspaper's hideous, half-naked women to glimpse the sublime through music, opera, the pictorial and plastic arts or literature, then they will never look at the Sun again. It is the Sun's function to keep its readers ignorant and smug in their own unpleasant, hypocritical, proletarian culture.

Undeterred, Britain's best-selling tabloid gallantly mourned his passing. ‘Good Man’ was the heading in its leader column that day:

Auberon Waugh, who has died at the age of 61, was a writer and journalist with a unique and wonderful talent.

True he occasionally used his talent to attack the Sun. But his wit shone like a beacon. We suspect he loved us as much as we loved him.

Our sympathies are with his family. His was a great life lived well.

If this was remarkable the Daily Telegraph, a paper for which he had worked for nearly forty years, elected to treat his death as though it were the outbreak of World War III. A top front-page news story (‘Auberon Waugh, Scourge of the Ways of the World, Dies at 61’) propelled its readers on a five-page binge-tour of his life and work, complete with portraits, obituaries, quotations, adoring reminiscences and amused commentaries.2 A. N. Wilson, in a piece entitled

‘Why Genius Is the Only Word to Describe Auberon Waugh’, put down a marker for his immortality:

He will surely be seen as the Dean Swift of our day, in many ways a much more important writer than Evel

yn Waugh. Rather than aping his father by writing conventional novels, he made a comic novel out of contemporary existence, and in so doing provided some of the wisest, most hilarious, and – it seems an odd thing to say – some of the most humane commentary of any contemporary writer on modern experience.

I was pleased by these sentiments, even though Wilson's use of the word ‘important’ spoils the thing a little. My father, who spent his life vigorously lobbing brickbats at the whole muddled notion of ‘importance’, would have laughed at the idea of himself as an ‘important’ writer.

My various solutions to the problems which beset the nation are intended as suggestions to be thrown around in pubs, clubs and dining rooms. If the Government adopted even a tenth of them, catastrophe would surely result.… The essence of journalism is that it should stimulate its readers for a moment, possibly open their minds to some alternative perception of events, and then be thrown away, with all its clever conundrums, its prophecies and comminations, in the great wastepaper basket of history.

If journalism was not ‘important’ to him he nevertheless held it, as a profession, in high regard. It was only when journalists took their jobs too seriously, when they tried to play an active part in shaping events, that he began to lose his enthusiasm for the press. The sole purpose of political journalism, he always insisted, was to deflate politicians, the self-important and the power mad: ‘We should never, never suggest new ways for them to spend money or taxes they could increase, or new laws they could pass. There is nothing so ridiculous as the posture of journalists who see themselves as part of the sane and pragmatic decision-taking process.’

One such figure was Polly Toynbee, a hardened campaigner of the ‘liberal left’, whom Papa had long regarded as the preposterous embodiment of all that is most self-important, humourless and wrong-headed within his own profession. She was stung by the glowing obituaries he received and decided, while his body was still awaiting interment on a mortuary slab in Taunton, to launch an impassioned counterblast in the Guardian. The effect of this could not have been more explosive or more satisfactory. Just as I feared the press was about to wander from the subject, as the bleak prospect of a January burial was all that lay ahead by way of comfort to the grieving, a new fire was ignited: Papa was briefly revivified.

Toynbee's piece cannot be easily summarised because its gist was clouded by too many swipes at her enemies among the living. If her readers were either hoping for or expecting a prize-fight between Ms Toynbee and a dead man they must have been disappointed: all they got was a bewildering mêlée of emotional ringside scraps. What was it all about? Well, at the root of Ms Toynbee's article could be heard a distant wail of indignation, not so much at Auberon Waugh himself as at his influence. This she termed ‘the world of Auberon Waugh’, and characterised as ‘a coterie of reactionary fogeys … effete, drunken, snobbish, sneering, racist and sexist’. Her article caused a nationwide explosion of support for the deceased. ‘Never,’ wrote the eminent Keith Waterhouse in his Daily Mail column, ‘never in a lifetime spent in this black trade have I read a nastier valedictory for a fellow scribe.’ ‘Polly put the kettle on,’ howled the Telegraph's leader writer, while the New Statesman hit back with: ‘Polly Toynbee is wrong. The writer she reviled as a “ghastly man” should be celebrated alongside George Lansbury and Fidel Castro as a hero of the left.’

I swung my own fist into the ruckus with a riposte published on the letters page the following day:

In an earnest piece (Ghastly Man, January 19) Polly Toynbee registered her views on the death of a humorous journalist a few days ago. ‘We might let Auberon Waugh rest in peace,’ she heaved, ‘were it not for the mighty damage his clan has done to British political life, journalism and discourse in the post war years.’

This was illustrated by a drawing of my father's corpse being washed down a lavatory, in much the same way as pee, paper and faecal matter is sluiced on a daily basis. Regular readers, who respect the Comment & Analysis pages, may have thought that the illustration was to be taken equally seriously as Ms Toynbee's high-minded and heartfelt article. Rest assured.

Auberon Waugh's ‘clan’ does not intend to compound the ‘mighty damage’ it has already done to this country by disposing of his body in this unhygienic manner. We shall ensure that all health and safety regulations are observed when the great man is buried in Somerset on Wednesday.

If you judge my letter to have been a little low on emotion, consider another from someone called Eamonn Duffy from Welwyn in Hertfordshire which appeared next to mine on the same day:

My immediate reaction on hearing of Waugh's death was to punch the air and exclaim, ‘Good riddance!’ But Polly Toynbee's reply to all the sickly and sycophantic obituaries put into words exactly how I really felt about this vile man.

The funeral was not as sombre as perhaps it might have been. The service took place three miles from Combe Florey in an Anglican church that was big enough to accommodate the hordes of friends, family, fans and newspapermen who were expected to attend. Many of them had been reminiscing about my father in the bar of the Paddington to Taunton express and arrived as a gabbling pack under a warm halo of intoxication. The sun shone as the cortège proceeded through Bishop's Lydeard where, every forty yards, a stationed police officer bowed his head in deference to its passing. Two sergeants saluted the coffin from either side of the churchyard gate as it entered. Papa, I know, would have been thrilled by this:

The police, like most government departments nowadays, are chiefly concerned to look after themselves. They have no interest in apprehending burglars, tending to blame the house-holder, and small enough interest in the victims of mugging. When they rush around in vans, nine times out of ten they are rushing to the relief of a colleague who has reported threatening behaviour from a drunk – the offence itself provoked by the presence of a policeman in the first place.

For forty years the police were a target of his ridicule. Now the very force he had lambasted as idle, cowardly, oafish and self-serving had assembled itself in great style, and on overtime pay, to salute his coffin.

Uncle James Waugh dignified the proceedings by reading in an aptly lugubrious, basso tone from the Book of Wisdom:

The virtuous man, though he die before his time, will find rest.

Length of days is not what makes age honourable,

Nor number of years the true measure of life;

Understanding, this is man's grey hairs…

One of Papa's favourite songs – a ghost's courting ode from Offenbach's Orphée aux Enfers, which he used to sing out of tune with a glass of port balanced on his head – was sublimely sung in the tenor register from the pulpit: ‘Oh, do not shudder at the notion, I was attractive before I died.’ After that my brother and I took it in turns to read passages from Papa's journalism. Originally I wanted a piece from his diaries in which he had lamented the summer invasion of Somerset by tourists from the Midlands. On consideration, it was probably not such a grand idea for a funeral:

The roads of West Somerset are jammed as never before with caravans from Birmingham and the West Midlands. Their horrible occupants only come down here to search for a place where they can go to the lavatory free. Then they return to Birmingham, boasting in their hideous flat voices about how much money they have saved.

I don't suppose many of the brutes can read, but anybody who wants a good book for the holidays is recommended to try a new publication from the Church Information Office:

The Churchyard Handbook. It laments the passing of that ancient literary form, the epitaph, suggesting that many tombstones put up nowadays dedicated to ‘Mum’ or ‘Dad’ or ‘Ginger’ would be more suitable for a dog cemetery than for the resting place of Christians.

The trouble is that people can afford tombstones nowadays who have no business to be remembered at all. Few of these repulsive creatures in caravans are Christians, I imagine, but I would happily spend the rest of my days composing epitaphs for them in exchang

e for a suitable fee:

He had a shit on Gwennap Head,

It cost him nothing. Now he's dead.

He left a turd on Porlock Hill

As he lies here, it lies there still.

In the end I chose a more fitting epicedium, one that rails against the young, against television and against junk food. I remember his coming into the kitchen asking what modern muck young people were currently eating. It was always a thrill to be able to help him with information for his articles. ‘Brilliant! Goodness, you are brilliant!’ he would say, if I succeeded. Usually I failed and he would leave the room with a look of disappointment, but on this occasion I clearly remember his delight. The result, a simple list, was painfully funny to a fifteen-year-old at the time and to a packed church of mainly middle-aged mourners twenty years later, it shone in pristine glory:

The best things on television this summer are the National Health Council advertisements warning parents not to overfeed their disgusting, football-like, toothless children.

Over half the population of Britain is overweight. The main reason is that it sits in front of the television all day, watching advertisements. This is the average diet of your typical, spherical, 14½-year-old British kiddy, usually of indeterminate sex:

Breakfast:4 Crunchie bars; 3 fish fingers; 1 pkt Coca-Cola flavour Spangles; 1 tin condensed milk; 2 btles Fanta.

Elevenses:3 Mars bars; 2 artificial cream buns; 1/2 pt peppermint-flavoured milk; 3 pkts Monster Munch multi-flavoured crisps.

Luncheon:3 fish fingers; 2 Twix bars; 1 tin fruit salad; 17 tea biscuits; 1/2 pt brown sauce; frozen peas.

Afternoon subsistence:2lb Super-Bazooka chocolate flavour bubblegum cubes; 1 tin condensed milk; 2 small btles strawberry flavoured Lip-Gloss.

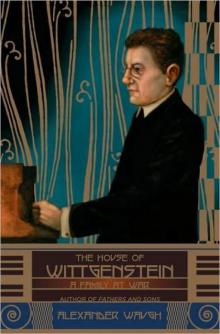

The House of Wittgenstein: A Family at War

The House of Wittgenstein: A Family at War Fathers and Sons

Fathers and Sons